AN OVERVIEW MANAGEMENT OF OBESITY IN PRIMARY HEALTH CARE CENTER: LITERATURE REVIEW

Anuod Salem Alrehaily1, Jehan Ghazi Alhelali2, Ehdaa Khalid Boudal3, Taibah Mahfouz Alhamzah2, Mohammed Ghalab Alanazi4, Alzilfi Abdulrahman Saleh S5, Hussam Atallah Atallah3, Abdullah Fahad Alhejaili3, Amro Abdulhaleem Noorwali6, Sultan Abdulaziz Alsehli6*

|

|

|

ABSTRACT

Background: Obesity is a rapidly increasing disease in developed and developing countries. Almost 12% of adults around the world are considered obese. Obesity-associated with other serious illnesses puts the patient’s life in danger, as well as decreasing their quality of life. This disease has some known risk factors but the exact pathophysiology remains a mystery need to be solved. Objectives: We aimed to review the literature reviewing the etiology of obesity, risk factors, diagnosis, complication, and management of this disease. Methodology: PubMed database was used for article selection, gathered papers had undergone a thorough review. Conclusion: With obesity, multiple other diseases emerge as well; which in their turn aggravates the disease in a vicious cycle. The management plan of each patient is unique, depending on the patient’s background, comorbidities, degree of obesity, and level of cooperation. Serious complications can be avoided by weight loss, even if it was minimum. With a variety of treatment options in hand, the family physician should explore and discuss this matter thoroughly with the patient to reach optimum outcomes.

Keywords: Obesity, Diet, Weight Loss, Diabetes, Gastric Sleeve, Overweight, Metabolic Syndrome.

Introduction

Obesity has become a nagging issue in almost every developed and even developing countries in the 21st century. With the rapid increase in prevalence worldwide, more consideration and efforts should be paid in the face of the uprising pandemic. In 2015, 107.7 million children and 603.7 million suffered from obesity; representing an overall prevalence of 5% and 12% respectively. [1] Locally, a recent study conducted in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia found that almost 55.3% of the random sample selected are considered overweight or more according to body mass index (BMI). [2] Obesity, usually, is not a standalone condition, it tends to come with the company of other serious comorbid diseases. Consequently, a more severe impact affects the health care system, economy, and most importantly individual’s quality of life [3-6]. As obesity is considered a multifactorial disease, a holistic approach in management is required. Tackling every, and almost all, contributor factors to reach a fruitful outcome. Family physicians are the first line defender in that regard, thence comprehension understanding among them is an essential asset they should have.

Methodology

PubMed database was used for the selection process of relevant articles, and the following keys used in the mesh ((“Obesity"[Mesh]) AND (“Diagnosis"[Mesh] OR "Definition"[Mesh] OR "Risk factors"[Mesh] OR "Management"[Mesh])). For the inclusion criteria, the articles were selected based on including one of the following: obesity or ectopic obesity risk factors, evaluation, etiology, pathophysiology, consulting, management, and diagnosis. Exclusion criteria were all other articles that did not meet the criteria by not having any of the inclusion criteria results’ in their topic.

Review:

Obesity Definition and Classification

Definition of obesity according to the World health organization is “a condition in which percentage body fat (PBF) is increased to an extent in which health and well-being are impaired”. In terms of objective measurement, body-max-index (BMI) is widely in use due to its easiness and cost-efficiency. Despite the popularity of BMI, some drawbacks emerged, for example, it neither can distinguish between fats, muscles nor bone mass. See table 1 for the cut-off value of each BMI category. [7] Other accepted indirect anthropometric measures include waist circumference (WC), waist-hip ratio (WHR), and estimated body fat percentage captured by skinfold thickness (ST). [8]

Table 1. Body-mass-index categories in adults

|

Category |

Value (kg/m2) |

|

Underweight |

< 18.5 |

|

Normal weight |

18.5-24.9 |

|

Class I obesity - overweight |

25.0-29.9 |

|

Class II obesity - obesity |

30.0-39.9 |

|

Class III obesity - extreme obesity |

> 40 |

|

|

|

Risk Factors and Pathophysiology:

Different factors contribute to weight increase and to what extent will it be. Various combinations of underlying factors would give similar results even if they are not present all together in all affected population. In simple words, obesity results when the calorie intake exceeded the calorie expenditure. An increase in food quantity or calorie-dense food, like sugar-sweetened beverages, will rise the first part of the equation, while the latter part is prone to hormonal regulation and physical activity. One’s genetic profile, previous and current medical history, and medication in use can precipitate weight gain or, on the contrary, weight loss. Psychological well-being and sleeping pattern have a major effect as well. Apart from the patient’s factors, the environment has its fair share in disease-evolution complex. Studies have associated limited access to physical activity resources, walkable neighborhoods, and educational institutions with obesity. Moreover, poverty and obstructed access to healthy fresh groceries showed similar results. [9]

Regulation of satiety and hunger is orchestrated by multiple hormones produced by the gastrointestinal tract. Where the only identifiable orexigenic is ghrelin, a peptide hormone derived from the stomach. Many hormones are contributing to causing the feeling of fullness. Peptide YY (PYY), cholecystokinin (CCK), oxyntomodulin, glucagon-like peptide-1, and leptin are all involved in the anorexic sensation felt by the normal population after consuming a meal. Any disturbance of the harmony would lead to an imbalance of the satiety center, hence more food will be ingested. Some diseases and drugs interfere with the aforementioned processes and induce obesity, like exogenous corticosteroid and endocrinal imbalance in hypothalamic, pituitary, thyroid, or adrenal gland level. [10]

Comorbidities and Complications:

With the excess adiposity found in obesity; the body has a hard time sustaining normal function while coping with this troublesome disease. Coexisting diseases emerge as a result of obesity while at the same time they aggravate obesity in which can be explained by the “vicious cycle model”. Adiposity results in complications through anatomical and metabolic effects.

Visceral obesity induces a lot of metabolic changes to work potently in inducing proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1, and IL-6, which in their turn promote metabolic disorders. Insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, among others are associated with metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is defined as the presence of insulin resistance in addition to two of the following risk factors: obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, or microalbuminuria. [11-13]

Type 2 diabetes millets (T2DM) is triggered by weight gain, especially visceral fat around the pancreas and the liver. Fat distribution patterns and BMI can be used in the assessment of visceral fat, but the most preferable measurement tools are waist circumference (WC) and waist-hip ratio (WHR). According to one study, having a BMI of 30-35 kg/m2 was associated with five times increased risk of developing T2DM. This increase can reach up to 12 times higher in those with a BMI of 40–45 km/m2. As a result, a reduction in weight, especially in the visceral fat surrounding pancreas and liver, promotes the remission of T2DM. [11, 12, 14]

Coronary heart disease and its sequelae myocardial infarction are no doubt associated with obesity. WHR measurement is a good predictor of both diseases and it shows an apparent correlation in comparison to BMI. As central obesity is one of the metabolic syndrome pillars, the cardiometabolic risk is increased. One major complication of cardiovascular diseases is stroke, where obese individuals (BMI > 30 kg/m2) had a 64% increased risk of having an ischemic stroke. [12]

Obesity is the most common risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in both men and women. This is resulted because of pharyngeal collapse due to upper airway adiposity and increased neck circumference. Class I is associated with a 5-times increased risk of OSA, while class II obesity is associated with a 22-times risk increase. Symptoms of OSA are morning headache, systemic hypertension, and can eventually result in pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure. These repeated symptoms can lead to excessive daytime somnolence, negatively affect work performance. [11, 12]

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its sequala non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can progress to liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can result from obesity as both BMI and WC showed independent correlation with NAFLD. Presentation of this group of diseases includes hepatomegaly, abnormal liver function tests, and abnormal liver histology. [11, 12]

Approach to Weight Loss:

Obesity and weight loss issues might not be addressed by the patient directly, which can be explained by the overall stigma toward the disease and how society is dealing with it. Moreover, obesity counseling by family physicians shows a declining pattern over the years. The underlying cause is the physical absence of motivation due to a lack of confidence in their counseling skills and having low outcome expectations as a prejudice. Despite all that, the patient still assumes that the doctor would address the topic of weight if needed. Otherwise, they would not be aware of the problem. [15]

To assess the weight status of a patient, objective measurement is needed. Body-mass-index is commonly in use and provides valuable information. See table 1 for more information. Another tool of assessment is waist circumference where it shines in a patient who is overweight but otherwise healthy so a prediction of possible complication can be made. A waist circumference ≥ of 88 cm for women and ≥ 102 cm for men, echoes the abundance of abdominal visceral fat and forecast greater weight-related health risks. If the patient turned out to be obese, a further detailed and thorough history taking and physical examination are required. As their findings well explore the possible complications and comorbidities which in their turn will draw the outlines for setting a suitable management plan. It was also important to step by the medications history and to document those that were in use before and the current ones, and their possible contribution to the patient’s current status. Psychological assessment is also a cornerstone when it comes to obesity assessment, addictive behaviors, mood disorders, and eating disorders such as bulimia, binge eating, and night eating are all significant health issue that may mandate referral to a professional. [16] The specific system-oriented examination shall be performed by targeting special signs and symptoms of possible comorbid diseases. For example, elevated blood-pressure or acanthosis nigricans can be used to predict the risk for hypertension and diabetes. While there are no specific laboratory tests for obesity, current guidelines recommend universal lipid and blood sugar screening in overweight patients. [16]

Explaining the consequences and the current situation to the patients is a fundamental step in managing their condition. The patient should fully understand the benefits that they will gain after losing weight and how can they do so. Setting long term outcomes without short term would usually lead to loss of interest and continuation. As patients may think they have to lose a significant amount of weight before noticing any difference, only 5-10% weight reduction can improve the overall quality of life, reduce aches, and improve blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar. Highlighting some noticeable changes by the patient, like erectile dysfunction or inability to conceive due to polycystic ovarian syndrome might draw a patient’s attention. [16]

The 2013 Guidelines for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults suggested an algorithm of three steps to choose between behavior modification, weight-loss medications, and surgery: [16]

Lifestyle Modifications:

Regardless of which category of obesity the patient falls in, behavior modification with frequent follow-up is a fundamental step. The broad outcome of lifestyle modification is to reach a negative energy balance by modifying both diet and activity. Three proposed approaches in dieting are recommended, a plan with 1,500 kcal/day for women and 1,500-1,800 kcal/day for men, adjusting as needed. Second, a calorie deficit of 500-750 kcal/day, and lastly, prescribe a diet that restricts certain components of foods such as high-carbohydrate, low-fiber foods, or high-fat. Recommendations regarding physical activity include endurance improvement up to moderate-to-vigorous physical activity 30 minutes/day most days of the week (>150 minutes/week). [16]

Patients should be encouraged to improve their self-monitoring skills, by recording the type of foods and beverages consumed, their calorie intake, and weight gain or loss would help them to identify their eating habits and what is good and what is bad for their diet. Avoiding triggers such as the smell or sight of food, as well as, places, and times associated with eating, like chips bags and chocolate bars to be hidden from visible kitchen racks would result in less overeat. Setting measurable goals is important, as it would help the patient to capture the progress and regress in their status. Finally, teaching the patient how to solve the problem instead of caving for them would promote their adherence. For instance, if the patient has overeaten on one occasion, instead of feeling guilty they can burn the excess calorie out by doing some exercises. [17]

The follow-up pattern recommended by the guidelines is in-person meetings at a rate of at least twice monthly in the first six months. If the frequent in-person visits are not readily feasible, an alternative should be considered via telecommunication media such as telephone or internet. [16, 17]

Pharmacological Options:

The pathways are targeted by the pharmacological agents are located in the brain and gastrointestinal tract (GIT). Neurotransmitters including monoamines, amino acids, and neuropeptides, are involved in regulating the satiety center. Serotonin 5-HT2C receptors, located in the GIT, control fat and caloric intake. α1-Receptors and α2-receptors also play a role in modulating feeding. Moreover, Activation of β2-receptors in the brain reduces food intake, thence β-blocker drugs promote weight gain. Other drugs act in the periphery such as orlistat which blocks intestinal lipase will produce weight loss. While Glucagon-like peptide-1 acts on the pancreas and brain to reduce food intake. Amylin is secreted from the pancreas and can reduce food intake as well. [18]

FDA approved medication for weight management can be divided into two groups. First, long-term treatment of obesity includes orlistat, lorcaserin, liraglutide, the combination of phentermine/topiramate, and the combination of naltrexone and bupropion. The second group consists of sympathomimetic drugs that are FDA approved a long time ago for short-term use only, usually considered <12 weeks. See table 2 for details of pharmacological options. [17]

Table 2. FDA-approved drugs for weight loss

|

Generic name |

Trade names |

Usual dose |

|

FDA-approved long-term treatment of obesity (12 months) |

|

|

|

Orlistat |

Xenical |

120 mg 3 times/day |

|

Sibutramine |

Reductil |

5-15 mg once daily |

|

FDA-approved short-term treatment of obesity (12 weeks) |

|

|

|

Diethylpropion |

|

|

|

Tablets |

Tenuate |

25 mg 3 times/day |

|

Extended-release |

Tenuate |

75 mg in the morning |

|

Phentermine HCl |

|

|

|

Capsules |

Phentridol, Teramine, Adipex-P |

15-37.5 mg in the morning |

|

Tablets |

Tetramine, Adipex-P |

15-37.5 mg in the morning |

|

Extended-release |

Ionamin |

15 or 30 mg/day in the morning |

|

Benzphetamine |

Didrex |

25-150 mg/day in single or divided doses |

|

Phendimetrazine |

|

|

|

Capsules, extended-release |

Adipost, Bontril, Melfial |

105 mg once daily |

|

Tablets |

Prelu-2, X-trozine, Bontril, Obezine |

35 mg 2–3 times/day |

Surgical Options:

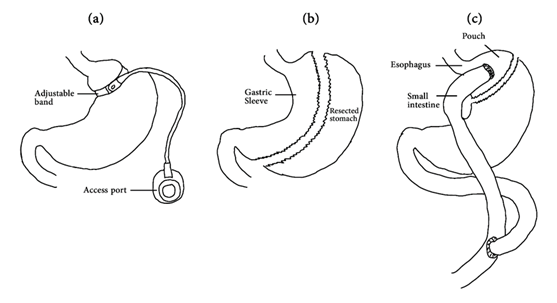

The last resort for severely obese patients is surgery; as above-mentioned criteria, eligible patients are those with a BMI of ≥40 kg/m2 or patients with a BMI of ≥35 kg/m2 with comorbidities. The surgical procedures rely on restrictive, malabsorptive, or combination procedures to achieve the optimum outcome. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery achieves its goal of weight loss by restriction causing early satiety, malabsorption, as well as hunger reduction because of the decrease in ghrelin production and increased PYY. Sleeve gastrectomy, where a linear cutting stapler makes a new-shaped stomach along the lesser curvature, results in loss of 75% to 80% of the gastric body and fundus. It has a better outcome in comparison to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in terms of reducing the risk of micronutrient deficiencies and peptic ulcer disease. Finally, Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding is a purely restrictive procedure, in which the fundus of the stomach is wrapped with a small silicone band. The major perk of this procedure is the ability to adjust after placement according to the patient’s need. Figure 1 demonstrates the 3 mentioned surgeries. [10, 17]

Figure 1. The most common three bariatric surgeries. (a) a laparoscopic gastric band (b) Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (c) Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.

Conclusion:

Obesity imposes health risks among the affected population, as well as the health care system causing exhaustion of resources. Obesity is related to the number of cardiovascular, metabolic, and respiratory disease which hinders patients’ quality of life. A tailored management plan that suits the specific patient and meets their goals is an essential cornerstone in the treatment journey. The treating physician must follow up on the case and mark the progress and identify the obstacles in the road. Weight loss, even if minimum, would enhance a patient’s life, increase their efficiency, and boost their self-esteem. Setting “reasonable” goals within a “reasonable” time fall in the physician duty, as patient tend to exaggerate their hopes and potential which would lead to adverse outcomes instead.

References