The Prevalence and Factors Influencing the Crown Rectification or Remake Need

Mohammed Al-Rafee 1, Fahad Mohammed Alotaibi 2*, Abdulrahman Alammari 2, Nawaf Alrafee 2, Abdulla Alkhashman 2, Abdalelah Bahmaid 2

|

|

|

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Prosthodontic rehabilitation of teeth using crowns has seen several advances over the past couple of decades. Nevertheless, clinicians are still receiving crowns from a laboratory that may require varying degrees of correction or remaking. This study evaluated the clinicians' considerations in determining the prevalence of the need for rectification or remaking of crowns and the factors that influence them. Materials and Methods: The instrument for the study was a modified version of a previously adopted questionnaire. Through the questionnaire, each clinician collected demographic data and specific information about the level of acceptance or rejection. A Chi-square test was performed to explore the difference between the study characteristics and crown assessment categories. Post comparisons were performed with a z-test adjusted by the Bonferroni correction. Results: Proximal contact deficiency (35%) constituted the main reason for laboratory rectification of crowns, followed by shade mismatch (27%). Zirconia crowns were seen to have more clinical acceptance (70%) at the time of fit-in, while PFM crowns, by and large, either required adjustments or remake (86.2%). Specialists were more inclined to accept crowns or adjust them clinically (70.1%). Clinicians with more than ten years of experience were less likely to order a crown's remaking (5.7%). Conclusion: Rectification or remaking of crowns in the laboratory was found to be of sizeable quantity. The requirement for further adjustment of crowns in the laboratory was primarily due to proximal contact deficiency. The remaking of crowns was mostly mandated owing to the poor fit of crowns. Specialists and clinicians with more experience were less likely to have crowns remade and managed with chairside adjustments or in the laboratory.

Keywords: Crown fit, Misfit, Shade matching, Remake, Rectification.

Introduction

The replacement of teeth or parts of teeth using extra-orally fabricated prostheses has seen several advances over time. The success of these dental prostheses involves their fabrication with minimal errors, mechanically, and esthetically.

Dentists continually face the dilemma of receiving clinically unacceptable crowns from the laboratory, thereby wasting both their and the patients' time. While most dentists have reported a crown remake rate of less than 2%, about 17% of them reported a remake rate of greater than 4%. [1] The reasons for remaking the crowns are diverse, and several authors have theorized numerous factors when determining crown acceptability. [2-6] Investigators in one clinical trial considered a marginal adaptation, proximal contact, occlusion, and ethics as the factors determining a crown's success.3 Reports considering the marginal adaptation of crown integrity have also investigated the internal adaptation of the crowns. [4, 5] Likewise, a similar study focused entirely on the clinical evaluation of proximal contact. [6]

The key players in governing a dental prosthesis's success are the dentist, the dental technician, and the patient. Miscommunication between the dentist and dental technician has often proved to be the causative factor for crowns requiring rectification or remake. [7] It has also been reported that patient expectations and esthetic demands play an essential role in prosthesis's acceptability and clinical success. [8, 9]

At the dentist's level, several procedural errors might influence the fabrication of a faulty prosthesis. These may involve varying skillsets and errors during preparation such as over or under reduction, over or under tapering, etc. [10] Furthermore, errors in shade matching, impression making, choice of materials, etc. can all affect the outcome. [1] The choice of gingival tissue management and technique before impression making is another important step within the control of the dentist. Sound isolation and retraction are mandatory to obtain an optimum impression. Obtaining a 0.2 mm gap between the gingival tissue and the finish line is essential and is attainable by both retraction cords and pastes, [11] although it has been debated that the techniques using the retraction cord provided more displacement. However, cordless techniques (paste) may have the advantages of patient comfort and fewer inflammatory markers. [12, 13]

Amidst this wealth of literature, there is inadequate information regarding the dentists' opinion about the prevalence of and factors influencing the need for crown rectification or remake.

The current study aims to evaluate the dentists' considerations in determining the prevalence of and factors influencing crown rectification or remake and further distinguish the common problems most dentists face during the fit-in appointment.

Materials and Methods

Research Instruments

The instrument used was a questionnaire incorporated and modified from two previous studies by McCracken et al. in 2017 and 2018. [1, 14] The questionnaire was divided into sections; the first part gathered demographic data about the type of practice, clinician's personal and qualification details, position, and crown type. The second section obtained information regarding the clinician's assessment of the crown's acceptability or lack thereof and the reasons for rectification or remaking of the crown. Specific criteria were followed, for either remake reasons such as poor-fitting, rocking or loose crown, etc., or requesting rectification such as shade mismatch, over-contoured crown, poor proximal contact, poor occlusal contact, etc. [14]

Ethical Clearance

The research proposal was submitted to the Research Center at Riyadh Elm University [FUGRP/2020/134/82], and the necessary ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Riyadh Elm University [FUGRP/2020/134/82/76].

Sampling

The study employed a convenient sampling technique to select participant dentists. It was conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, at governmental, private, and, academic clinical setups (hospitals and clinics).

The participants were selected based on education level, currently practicing and treating patients in Riyadh city, years of experience, and agree to participate in the study.

Each participating dentist evaluated the crowns and filled out the questionnaire. The questionnaires were numbered, and data encoded onto a Microsoft Excel sheet, and later transferred to specialized statistical analysis software.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of frequency distribution and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. A Chi-square test was performed to explore the difference between the study characteristics and crown assessment categories. Post comparisons were performed with a z-test adjusted by the Bonferroni correction. All statistical analyses were performed using the IBM Statistics SPSS Version 25.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

The questionnaires were distributed in different sectors in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. A total of 517 questionnaires were completed and accepted. From among the 517 responses 76.0% (n=393) were male clinicians and 24.0% (n=124) were female clinicians. From the total sample size, general dentists constituted 35.0%, postgraduate dentists constituted 22.2%, while specialists and consultants made up 42.7% of the participating clinicians. The private sectors contributed to the majority of the responses (54.4%), while the participants from the government sector (30.0%) and academic institutions (15.7%) took part, respectively. (Table.1).

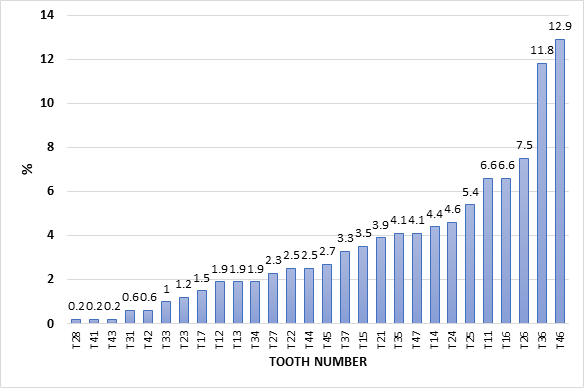

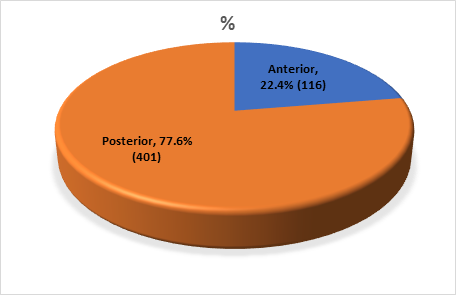

The study involved single crown restorations, of which 401 (77.6%) were made for posterior teeth, and 116 (22.4%) were made for anterior teeth (Figure 1). The Fédération Dentaire Internationale (FDI) system of tooth numbering was followed in the study. Lower first molars were the most restored teeth in the study, where tooth number 46 constituted 12.9%, followed by tooth number 36 at 11.8%. The second most restored teeth were upper first molars, where tooth number 26 constituted 7.5%, followed by tooth number 16, which constituted 6.6% (Figure 2).

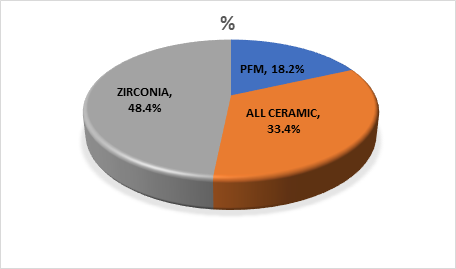

According to crown type restorations that were selected by participants, the majority were Zirconia crowns 250 (48.4%), followed by other all-ceramic crowns 173 (33.4%), and the least was porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns (PFM) 94 (18.2%) (Figure 3).

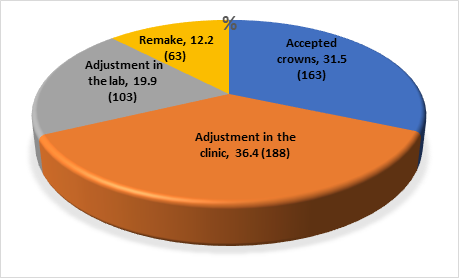

In the current study regarding the crown assessment, 163 (31.5%) crowns were accepted and ready without any modification/adjustment, 188 (36.4%) were accepted and ready for insertion after chairside modification. In comparison, the crowns that were not accepted and required further modification/adjustment in the laboratory were 103 (19.9%), and crowns that required remake/redo were 12.2% 63. (Figure 4).

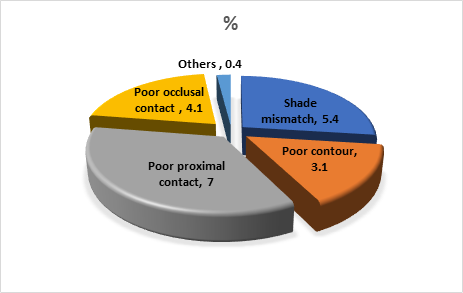

When the focus was placed on crown assessment for acceptability, the number of the crowns that were not accepted and required further modifications/adjustments in a laboratory were 103 (19.9%), for which the primary reason was poor proximal contact 36 (7%), followed by shade mismatch 28 (5.4%), poor occlusal contact 21 (4.1%), while poor contour was 16 (3.1%), and other reasons that were not mentioned 2 (0.4%) (Table 2).

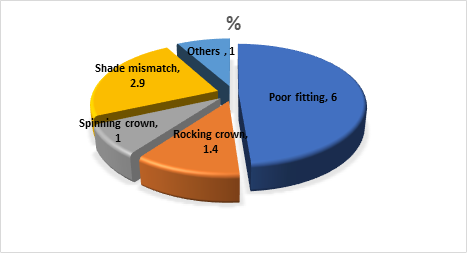

The number of crowns that were not accepted and required remake/redo was a total of 63 crowns (12.2%), for which the primary reason was poor-fitting 31 (6%), followed by shade mismatch 15 (2.9%), rocking crown 7 (1.4%), while each of spinning crowns and other reasons included 5 (1%) (Table 2).

When assessing the crowns that were sent back to the laboratory for further modifications/adjustments (n=103), the reasons, in descending order of prevalence, were Poor proximal contact (35%), Shade mismatch (27%), Poor occlusal contact (21%), poor contour (15%), and other reasons (2%) (Figure 5).

When assessing the crowns that were rejected and required remake/redo (n=63), the reasons, in descending order of prevalence, were Poor-fitting (49%), Shade mismatch (24%), Rocking crown (11%), Spinning crown (8%), and other reasons (8%) (Figure 6).

Regarding the location of the crown in the oral cavity, for anterior crowns, it was found that acceptance without corrections was the highest (39.7%), followed by acceptance with chairside adjustments (24.1%), then rectification in the lab (19%) and the least were remakes (17.2%). Posterior crowns showed a different pattern, wherein acceptance with chairside adjustments (39.9%) was the most common, followed by acceptance without corrections (29.2%), then rectification in the lab (20.2%), and the least were remakes (10.7%) (Table 3).

Acceptability based on crown types showed that Zirconia crowns by and large were accepted more (70%), either without correction (38.4%) or with chairside corrections (31.6%). Zirconia crowns requiring rectification were at 19.2%, while complete rejection and remake were least seen at a rate of10.8%. All-ceramic crowns showed a similar overall acceptance without lab intervention rate (69.4%), of which chairside corrections (38.2%). Those requiring laboratory interventions were at 20.2%, while 10.4% required remaking. PFM crowns saw the least acceptance without correction at 13.8%, while crowns requiring laboratory rectification were 21.3%, and remake was 19.1% (Table 3).

Regarding the level of education, it was seen that an overall clinical acceptance, with or without chairside adjustments, was higher for GPs (72.9%) and Specialists/Consultants (70.1%) when compared to Postgraduates (55.7%). Within each cadre, Postgraduates showed a higher remake rate (23.5%) than GP's or Specialists/Consultants, and it was statistically significant (Table 3).

When the focus was placed within each work area subgroup, both the Private and Government sectors showed a similar distribution wherein acceptance with clinical adjustment was highest. Rectification in the laboratory and least scores was given to remaking the crown entirely. Contrarily, the Academic sector showed a different pattern, in which crown remake rates were highest (38.3%), followed by laboratory rectification (32.1%), and least of all was the acceptance without any correction (9.9%). (Table 3).

Concerning the years of experience, it was seen that as the experience increased, clinicians accepted cases better, with or without adjustments, and relied less on the laboratory intervention to rectify or remake the crowns. Clinicians with 1-5 years of experience deemed crowns required laboratory rectification in 24.9% of the cases and remade for 19.7% of cases. Practitioners with more than ten years of experience relied on the laboratory less and reported laboratory rectification in only 16.6% and remake in 5.7% within their cadre (Table 3).

Discussion

The inevitable truth of extra-orally fabricated prostheses is that errors occur in many aspects, despite advancements in clinical and laboratory materials, techniques, and technology. The present study addressed these aspects from the dental practitioners' point of view.

It was found that 19.9% of the clinicians in the study accepted that the crowns could be cemented after certain laboratory modifications. From the crowns considered for laboratory adjustments, the most common reason was the proximal contact discrepancy (35%). This was in concurrence with a study conducted by McCracken et al. (2018). [14] Our study showed that 12.2% of participants rejected the work as unacceptable and requiring remaking of which the main reason for rejection was poor fitting crowns (49%). A poor-fitting crown is considered a crucial issue that could lead to further complications such as periodontal diseases, carious lesions, occlusal disharmonies, etc.

In an era where esthetics is the paramount consideration for patients, crowns' shade matching to their natural counterparts plays an active role in their acceptance or rejection. The current study found that shade matching was the second highest factor when considering a crown to require either modification (27%) or remaking (24%). A study conducted by McCracken et al. (2018) [13] stated that esthetic failures were among the most common reasons for rejection of a crown. These findings coincide with Shah et al. (2014) [15], where they emphasized the importance of tooth color in patients' satisfaction ratings across different age groups.

The crowns requiring further modifications/adjustments in the clinic were significantly higher in posterior teeth, possibly to assure a more stable occlusion.

In the crown type assessment, PFM crowns, in most circumstances (86.2%), required some modification, either in the clinic (45.7%) or laboratory (21.3%), or a complete remake rate (19.1%). Zirconia crowns showed more overall acceptability (70%), with minimal or no clinical intervention, which is most likely attributed to its superior fit.

While making an intra-comparison of each level of education, it was seen that Postgraduates showed a higher remake rate (23.5%) than GP's or Specialists/Consultants, which was possibly attributed to the higher quality outcome demanded under the supervision of their clinical instructors. Similarly, in terms of the work area, it was found that the rate of accepted cases was the lowest (9.9%) in the academic sector, which incidentally also showed the highest crown remake rate (38.3%). Both variables were statistically significant.

Experience in the field showed to have a positive influence on acceptance rates. The more experienced the clinician (more than 10 years), the more acceptance rate of crowns (37.8%) during fit-in visits and the less remake rate (5.7%), which was in agreement with McCracken et al. (2018). [14]

Limitations exist in this study. The primary outcome measure, clinical acceptability of the crown, is subjective and depends on each clinician's evaluation of that crown. The study was limited to single crown restorations alone.

Conclusion:

Within the limitations of the current study, it can be concluded that the Laboratory intervention for rectification or remaking of crowns is a significant issue with prosthodontic crowns. Factors that primarily influence the need for laboratory rectification are the proximal misfit and shade mismatch. Factors that primarily influence the need to remake a crown are poorly fitting and shade mismatch. Zirconia crowns showed a better acceptability rate than All-ceramic crowns. PFM crowns required more adjustments, either clinical or laboratory. Specialists/Consultants and Clinicians with more than ten years of experience showed less tendency towards requesting remaking crowns and managed chairside adjustments to render a crown acceptable.

Financial Support and Sponsorship:

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

|

Table 1: Characteristics of the Study Participants (n=517) |

|||

|

Characteristics |

n |

% |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

393 |

76.0% |

|

Female |

124 |

24.0% |

|

|

Nationality |

Saudi |

360 |

69.6% |

|

Non-Saudi |

157 |

30.4% |

|

|

Specialty |

GP |

181 |

35.0% |

|

Postgraduate |

115 |

22.2% |

|

|

Specialist/Consultant |

221 |

42.7% |

|

|

Work Area |

Private |

281 |

54.4% |

|

Government |

155 |

30.0% |

|

|

Academic |

81 |

15.7% |

|

|

Experience |

1-5 |

213 |

41.2% |

|

<5-10 |

111 |

21.5% |

|

|

>10 |

193 |

37.3% |

|

Figure 1: Different Types of Teeth Examined in This Study

Figure 2: Different Types of Crowns Examined in the Study

Figure 3: Anterior and Posterior Teeth Examined in the Study

Figure 4: Crown Assessment

|

Table 2: Remake and Laboratory Adjustment of the Crowns |

|||

|

Remake and Lab Adjustments |

n |

% |

|

|

Crown Is not Acceptable Requires further Modification/Adjustment |

Shade Mismatch |

28 |

5.4 |

|

Poor Contour |

16 |

3.1 |

|

|

Poor Proximal Contact |

36 |

7.0 |

|

|

Poor Occlusal Contact |

21 |

4.1 |

|

|

Others |

2 |

.4 |

|

|

Crown Is not Acceptable Requires Remake (Redo) |

Poor-fitting |

31 |

6.0 |

|

Rocking Crown |

7 |

1.4 |

|

|

Spinning Crown |

5 |

1.0 |

|

|

Shade Mismatch |

15 |

2.9 |

|

|

Others |

5 |

1.0 |

|

|

Total |

166 |

32.1 |

|

|

Accepted Crown/Adjustment in Clinic |

351 |

67.9 |

|

|

Total |

517 |

100.0 |

|

Figure 5: Crown Is not Acceptable and Requires further Modification/Adjustment

(to be sent back to the lab)

Figure 6: Crown Is not Acceptable and Requires Remake (Redo)

|

Table 3: Cross-tabulation between Individual Characteristics and Crown Assessment |

|||||||||||

|

Characteristics |

Accepted Crowns |

Require Adjustment in the Clinic |

Requires Adjustment in the Lab |

Requires Remake |

Total |

||||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

|

Tooth Position |

Anterior |

46 |

39.7 |

28 |

24.1 |

22 |

19.0 |

20 |

17.2 |

116 |

100.0 |

|

Posterior |

117 |

29.2 |

160 |

39.9 |

81 |

20.2 |

43 |

10.7 |

401 |

100.0 |

|

|

P Value |

χ 2=12.486; df=3; p=0.006* |

||||||||||

|

Crown Type |

PFM |

13 |

13.8 |

43 |

45.7 |

20 |

21.3 |

18 |

19.1 |

94 |

100.0 |

|

All Ceramic |

54 |

31.2 |

66 |

38.2 |

35 |

20.2 |

18 |

10.4 |

173 |

100.0 |

|

|

Zirconia |

96 |

38.4 |

79 |

31.6 |

48 |

19.2 |

27 |

10.8 |

250 |

100.0 |

|

|

p Value |

χ 2=21.821; df=6; p=0.001* |

||||||||||

|

Specialty |

GP |

63 |

34.8 |

69 |

38.1 |

31 |

17.1 |

18 |

9.9 |

181 |

100.0 |

|

Postgraduate |

24 |

20.9 |

40 |

34.8 |

24 |

20.9 |

27 |

23.5 |

115 |

100.0 |

|

|

Specialist/Consultant |

76 |

34.4 |

79 |

35.7 |

48 |

21.7 |

18 |

8.1 |

221 |

100.0 |

|

|

p Value |

χ 2=22.453; df=6; p=0.001* |

||||||||||

|

Work Area |

Private |

109 |

38.8 |

110 |

39.1 |

46 |

16.4 |

16 |

5.7 |

281 |

100.0 |

|

Government |

46 |

29.7 |

62 |

40.0 |

31 |

20.0 |

16 |

10.3 |

155 |

100.0 |

|

|

Academic |

8 |

9.9 |

16 |

19.8 |

26 |

32.1 |

31 |

38.3 |

81 |

100.0 |

|

|

P Value |

χ 2=87.420; df=6; p<0.001 |

||||||||||

|

Experience |

1-5 |

47 |

22.1 |

71 |

33.3 |

53 |

24.9 |

42 |

19.7 |

213 |

100.0 |

|

<5-10 |

43 |

38.7 |

40 |

36.0 |

18 |

16.2 |

10 |

9.0 |

111 |

100.0 |

|

|

>10 |

73 |

37.8 |

77 |

39.9 |

32 |

16.6 |

11 |

5.7 |

193 |

100.0 |

|

|

P Value |

χ 2=33.488; df=6; p<0.001 |

||||||||||

|

GP=General Practitioner, df=Degrees of Freedom, |

|||||||||||